There’s a common misconception about people with high pain tolerances. They tend to be big, beefy, and burly, usually men, and if female they’re all badasses. They shrug off bullets and sword-thrusts like they’re minor distractions; they grunt from the pain and rarely, if ever, scream.

There’s a common misconception about people with high pain tolerances. They tend to be big, beefy, and burly, usually men, and if female they’re all badasses. They shrug off bullets and sword-thrusts like they’re minor distractions; they grunt from the pain and rarely, if ever, scream.

Now, I frequently impress people around me with my high pain tolerance. Most of that is in awe; some few, such as my doctors and a close friend who helps me exercise, approach it with worry, because pain is an important thing. I have such a high pain tolerance that I often automatically ignore signals that I should really stop what I’m doing and rest. I threw out my back (a little over a year ago) and my knee (a couple months ago) precisely because I could just work through the pain . . . until I suddenly couldn’t.

How do I do that? Well, it’s not because I’m tougher than other people. I’m not beefy or burly, and I’m only big if I’m standing up and haven’t turned sideways. It’s never about your mass; it’s all about what you’re used to. Establishing that difference is the key to writing action heroes and other characters that deal with pain through the course of your story.

Experience

Pain is a matter of experience. The more bumps and bruises you get, not to mention more serious injuries, the more you’re able to ignore them. I’ve long since lost count of how many young children (and their parents) I’ve explained this to — that just because a crying toddler only suffered a minor bump doesn’t mean they’re overreacting. For a two-year-old, that one bump might be the worst pain they can remember experiencing.

Since pain is so subjective, it can be hard to comprehend. Every so often, someone will be trying to empathize with my pain by describing their own experiences — and then they realize that it’s not the same thing, so they try to backtrack. I tell them not to worry. “Just because I live with this on a daily basis,” I say, “doesn’t mean that your pain isn’t real. A bad day for you might be an average day for me — but it’s still a bad day for you.”

Part of that is from a societal expectation — the old “In my day, sonny . . .” descriptions of walking uphill both ways so we should be thankful for what we have. That’s true, but it gets in the way. We shouldn’t feel bad because we’re not experiencing the hardship of others (who wants hardship?); nor should we assume that all hardships are equal. Rather, the lesson to take from that is that, knowing that greater hardships have been overcome by others, we can look to them for inspiration on how to live with it.

This also happens with depression, which can — and should — be thought of as a spiritual or at least psychological pain, no less real than the physical variety. (Click here for another article I wrote on the topic.) Sometimes, whether due to good intentions or not, someone will point out that you shouldn’t be so sad because look at all the stuff you have going for you! Or, alternately (and even less effectively), look at all those people who have it worse than you. The reality is that telling someone their pain, physical or spiritual, isn’t worth anything because someone else’s pain is worse is exactly like saying that you can’t feel good because someone else is feeling even better. What you feel, right now, is what you have experienced. Short of telepathy, you can’t feel another’s pain, and you can’t feel another’s happiness.

It’s also important to remember that there’s no absolute value on pain. Just like the pain experienced by two people isn’t guaranteed to be equal, so too is the fact that people with high pain tolerances aren’t going to be able to shrug off new pain the moment it occurs. I have, as I said, a high pain tolerance; when my physical therapist is doing trigger-point therapy on me, I tend to experience bursts of pain; my reaction settles down quickly because it gets absorbed into the background pain I experience every day, but that reaction is still there. I still have to get used to the new normal. I don’t just shrug it off like it’s not there. No one does.

Kinds of Pain

What does pain feel like? Well, that’s a stupid question, isn’t it? Pain feels like pain.

Not really. Like with most things, if you spend enough time around it you start noticing differences. I can’t tell the difference between most wines, because I don’t drink wine. I experience a lot of pain, though, and I can tell you that pain comes in just as many subtle flavors as fermented grape juice.

Doctors define pain in six different ways. There’s tissue damage pain, which is the most common type and likely to be the one you write about in a story. This refers to any damage to the body, from bullets to bruises. If your character has a broken leg, arthritis, or a sprained wrist, it’s tissue damage pain.

Nerve pain is pain caused by messed-up signals; that can be caused by trauma to the rest of the body, but manifests as something different by the time the signals get to the brain — burning sensations when not on fire, or feeling the pain in a different place than the actual injury. This can be caused by medical conditions such as diabetes, by drug interactions, by strokes and heart attacks, and by regular old injury.

The third kind is psychogenic pain, which is caused or affected by your mental state. That’s not the same thing as “phantom pain,” but rather it’s physical pain that’s exacerbated or alleviated by your emotions. Depression, stress, anxiety, and other negative emotional states can make pain worse, far beyond the scope of the actual physical damage; while joy, relaxation, and other such things can have the opposite effect. As one example, I can’t normally stand for very long; but if I’m doing something I love, such as teaching or practicing with a sword, I can last a lot longer. For another example, just look at what happens when you put a preschool and a nursing home in the same building.

As the second video mentions, the Intergenerational Learning Center is a “discovery” that actually goes back to an older way of doing things, and it’s the more modern age-segregation that’s truly weird.

But back to pain. Each of the three types of pain I described above can be either acute or chronic. Acute pain is temporary, while chronic continues with little to no interruption, or has a repetitive nature beyond the scope of any physical interaction. Chronic pain usually starts off as acute, but not always.

But all of this is just what the doctors use to describe types of pain. Those who experience chronic pain of any kind, such as myself, know how there are many shades of difference between what different pains feel like. This is the part that authors have trouble describing, because even if they know what it feels like, they still have to explain pain to an audience that, presumably, isn’t feeling the same thing — and an audience that, presumably, doesn’t pay much attention to pain when it happens. Most people don’t. You try to forget pain as quickly as possible.

Pain can be sharp or dull, localized or over a wide area. It can peak during some movements but not others, and sometimes in unpredictable ways. Most injuries start off sharp, often with a burning sensation when flesh is torn or cut. A bone fracture feels like a cut as well, even if skin hasn’t broken.

Aches are usually dull, but can also create a pins-and-needles sensation. They can also suddenly manifest sharp, stabbing pain when moving too much or in the wrong way, and those pains can feel like they come from someplace else on the body due to muscle swelling causing pressure on key nerve clusters.

It’s also important to remember that adrenaline is a painkiller in the sense that it helps focus the mind on danger; so you’re conscious of pain, but it becomes easier to ignore. Once the adrenaline wears off, your character will feel rapidly worse — possibly exacerbated by involuntary tremors as their body flushes the excess hormone.

With experience, your character can self-diagnose. If you’ve experienced a broken bone before, especially several times, it becomes easy to tell the difference between a broken bone and a sprain. The same goes for bullet wounds, knife cuts, and other injuries your hero might have experienced before.

The harder thing to describe, of course, is the perspective of a character who has not experienced this sort of thing prior to your story. That’s where the 0-10 pain scale comes in.

Pain Scale

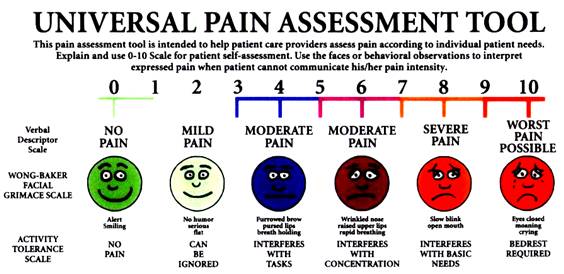

The pain scale is a common diagnostic tool, designed to give a nurse or doctor a yardstick for what you’re experiencing. I’m sure you’re all familiar with this or something that looks like it:

This isn’t intended to fit what you feel into some universal scale, but rather to diagnose how you feel, compare that to your injuries (if any are apparent), and then make an estimate on how much care you’ll need. One thing that helps, however, is for them to know what your 10 is.

I’ve been talking about my pain, so it’s time to explain it a bit. I have osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia. I also have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, for the extra fun that it entails. Pain and discomfort are daily companions, to the point that I’ve learned to ignore them (sometimes too well, as I described earlier). It also varies from day to day, so I’m never quite certain how I’ll be feeling. (Fortunately, my day job is very accommodating on this subject.)

When asked what fibro feels like, I describe it this way: Imagine your skin is on fire. (This is where some people blanch and look like they regretted asking the question.) Now imagine that the pain from that fire is frozen in the instant before your skin starts to blister. (This is where most people look like that first group.) Now imagine that pain is inside your skin, deep in the muscle, and doesn’t turn off. (Now everyone is wincing, including military vets who have received combat injuries.) Oh, and did I mention that I’m immune to most common painkillers? I’m even resistant to alcohol, opiates, and Novocaine (the latter made dental appointments awesome).

Generally speaking, the daily fibromyalgia pain — the fiery sensation that I just described, which isn’t really that accurate a description but it’s the best I’ve come up with — tends to be between a 5 and a 7 for me. So, since pain is affected by experience, you know that I’ve experienced worse than that. I had a bone infection a few years ago that wound up being all three kinds of doctor-definition pain (tissue damage, nerve, and psychogenic, the latter due to panic as they operated), and I’d classify that experience as a 9.

I’m sure you’re now wondering what my 10 is, and thinking that perhaps you don’t want to know. If you don’t, skip ahead two paragraphs. My 10 happened when the tip of my right middle finger was reattached without anesthesia. It took nine stitches, three of them in the nail bed. That was also the day I found out that I was allergic to lidocaine, the most common local anesthetic. It was a very unpleasant experience, and I experienced so much pain that I had to be reminded to breathe.

Ever wondered why pregnant women are taught to breathe on a rhythm, and why someone coaches them through it? I figured it out that day. If you’re experiencing that much pain, you need to focus on something. Breathing techniques are often part of pain management (it’s the most “automatic” function that can be consciously controlled by everyone, and so breathing can affect other things on the right rhythm), but in the middle of blinding pain you need something loud and sometimes “unnatural” to focus on. That day, one of the corpsmen had to coach me through something similar because I literally could not remember how to make my lungs work. (So seriously, the next time someone talks about men being able to handle more pain than women . . . men, they’re literally built for this. It’s a different kind of pain, but most adult women have done it at least twice. Try that on for size.)

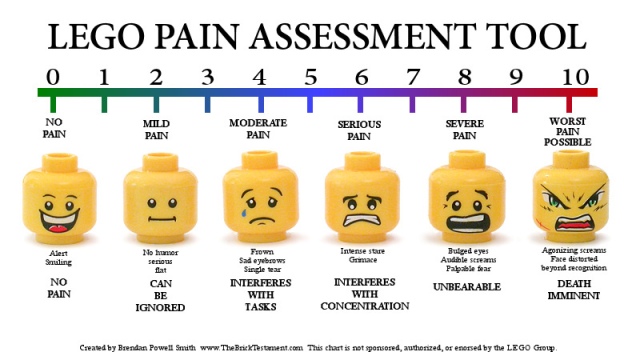

There are certain observable semi-universal reactions to pain that can be mapped on that pain scale up above, but everyone is a bit different. Let’s look at it again, with different faces this time.

Okay, yeah, it’s making a joke out of it, but if you have chronic pain you learn to laugh at it or you can’t get through the day. Plus, can you tell me that the normal frowny faces don’t seem silly? I think this version should be in children’s wards.

Anyway, the standard scale shows six faces, and often includes descriptions like what you see here (though this one is tailored for the Lego faces themselves). If you can figure out your character’s history — specifically, what physical injuries he or she has experienced over time — then you can use the 0-10 pain scale to figure out how that character would react.

The following is my pain scale. It’s a bit skewed, because most people (at least, most men and childless women) haven’t experienced what I call a 10 (nor would I wish them to). Because of that, I don’t advise using this specific scale for yourself or people you know. However, I do recommend using it for your characters as a whole. Any story where describing pain is an important point is probably a story where that level-10 pain has been or will be experienced by someone.

- 10: So painful that normally automatic functions (such as breathing or a regular heartbeat) might fail.

- 9: I can’t keep myself from screaming.

- 8: I can’t keep myself from making pained noises.

- 7: I can’t keep the pain from showing in my movements.

- 6: I can’t fully ignore the pain.

- 5: The pain is distracting.

- 4: The pain is annoying.

- 3: The pain is easily ignored.

- 2: I can feel it if I’m not concentrating on something else.

- 1: Meh.

- 0: Boy, these drugs are going to make me fall aszzzzzzzz . . .

This scale is pretty easy to apply to a POV character’s experience. If James Bond or Captain Kirk is having a level-6 kind of day, then he’s going to be slower when fighting the guy trying to kill him, but not by a whole lot; he’s trained to work with that kind of thing. If it’s an 8, though, it’s not only a danger to him, it’s also obvious to his enemies. If Harry Dresden is back home and trying to research the latest supernatural threat to Chicago after being thrown through a wooden wall, then he’s probably at a 7 and it’s interfering with his concentration. Meanwhile, if a less-experienced character is dealing with the same injury, you’d move it up the pain scale.

Characters in Pain

Living with pain is hard, but in some ways chronic pain sufferers have it better than those who get injured, recover, get injured again, recover again, and so on. The former will adjust faster than the latter. It’s a shock to suddenly go from 6 to 8, but it’s an even greater shock to go from 2 to 6. No one (barring severe nerve damage) can adjust to that instantly.

The more you experience it, however, the more the adjustment period shortens. One of the best portrayals of a tough, experienced-with-pain character is Mal Reynolds on Firefly. You can tell from multiple episodes that he’s suffered a lot of pain in his life, physical and emotional, and he’ll still react to pain like a normal person. He’ll yell when it hurts, scream when it hurts more, and then work through the pain once he’s adjusted his perception of the current situation to include the new hardship. In particular, Nathan Fillion does a great job of showing pained movements and having to adjust for injury. It’s a great credit to his acting skills.

Another great example of characters dealing with constant pain is in Elantris by Brandon Sanderson, a book I recommend even to people who aren’t fantasy fans because it’s a great example of many writing techniques I bring up when teaching. (If I could teach a full semester-long, credited course, Elantris would be required reading.) In the book, several characters are cursed with a magical affliction that not only keeps them from healing but keeps their bodies from changing. This means that every pain stays with them, as strong as the moment the injury occurred; a stubbed toe feels like a broken bone, and a sword through their gut results in a world of agony that they might never recover from, even though they can’t die. At one point, one such cursed individual took an injury protecting someone else, and when the other person reacted in horror, the first one simply responded that he’d bear the wound as a badge of honor because it was gained in a good cause. That literally brought a tear to my eye. (It’s worth reading for many other reasons than its description of pain, so just go get a copy. Trust me on this.)

For a nonfiction look at this sort of thing, you might check out Princess in the Tower, a website about chronic pain where people share their stories and try to describe what it feels like to other people. Even if you don’t need to delve into research right now, I’d personally like to recommend reading “This is What Chronic Pain Sufferers Want You to Know.”

Ultimately, while pain is subjective, the perception of pain winds up being pretty universal. Pain is an important tool, because it tells us (when things are working as they should) that something is wrong. It’s an everyday thing for everyone, to one degree or another, and so it’s important to describe it in a story. Most of us don’t think about it, but we’ll react to it nonetheless — because while we might not have the same injuries, we’ve all experienced pain; and we can imagine what others might feel with the right kind of prompting.

“Daredevil” is excellent at showing characters in pain. In particular the single take fight scene from episode 2 and the fight with Nobu were excellently acted by Matthew Cox. You could really see how much weaker he was getting.

As for Nathan Fillion, there’s a cool story from “Serenity” about his ability to act through pain. In the final fight with the Operative, we cut immediately from Zoe after the Reaver attack to Mal falling and slamming his head on the floor. The scene had to be reshot a great many time.

Everybody was impressed about how realistic Nathan made the fall look…and then they noticed that his face was swelling up. He wasn’t stage-diving, he was actually throwing himself to the ground. They actually had to stop filming to get Nathan ice and get his head back on straight, because he was getting woozy.

LikeLike

(Charlie Cox, sorry.)

LikeLike