I managed to find a little time this weekend to watch the first (and currently only) three episodes of the new show Agent Carter. I’ve been looking forward to this one for three reasons. 1) It stars Hayley Atwell as a gender-flipped James Bond figure. 2) It’s a 1940s period drama, and as both of my parents are WWII-era enthusiasts, I’ve picked up some of that myself. 3) It’s a Cold War spy thriller.

I managed to find a little time this weekend to watch the first (and currently only) three episodes of the new show Agent Carter. I’ve been looking forward to this one for three reasons. 1) It stars Hayley Atwell as a gender-flipped James Bond figure. 2) It’s a 1940s period drama, and as both of my parents are WWII-era enthusiasts, I’ve picked up some of that myself. 3) It’s a Cold War spy thriller.

I was not disappointed . . . well, in that regard. All three were basically what I was looking for, with enough extra twists to keep me surprised on all fronts. I didn’t need the Marvel Comics tie-ins to enjoy the show, though they helped with the suspension of disbelief when it came to the occasional anachronistic piece of tech. They even managed to deflect a bit of the Reed Richards is Useless trope by implying that the Stark family tends to have trouble inventing devices that are actually appropriate for civilian use, in a bit of a “go big or go home” vibe. That is, Howard Stark’s inventions don’t ever fail, they just turn out to be unexpectedly strong.

What I was disappointed with, however, was the same thing that is apparently driving male audiences away, though not to the same degree.

Agent Carter is a period drama staring a woman in the spy business, at a time when social attitudes about the proper roles for men and women hadn’t caught up to the reality of changing technology bridging the gap in physical capability between men and women.

Agent Carter is a period drama staring a woman in the spy business, at a time when social attitudes about the proper roles for men and women hadn’t caught up to the reality of changing technology bridging the gap in physical capability between men and women.

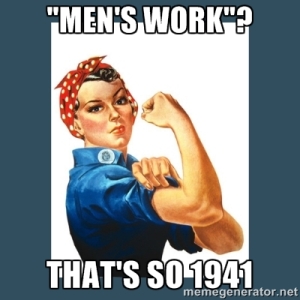

Once upon a time, the capability of the average man to, say, do a construction job far outstripped that of the average woman. By World War II, however, the difference had long since become academic — quite literally, as it had become rooted in what was appropriate and not what was efficient or possible. As more men left home to fight, women stayed behind and built their militaries’ weapons. It was a time of groundbreaking social change, far more important and wide-spread than even the aftermath of the previous World War. Rosie the Riveter wasn’t just a rallying cry, She was a proof of concept no one could honestly deny.

But rapid social change is difficult to adjust to, especially for men who had been overseas and didn’t realize just how all of that proof had been, in fact, demonstrated. The United States entered World War II fairly late, in December 1941. Germany and Japan both surrendered in 1945. Agent Carter opens in 1946. A lot has changed in five years, but it takes a while for it to really sink in. Everyone wants a return to normalcy, even the majority of women.

That’s where the worst anachronism comes in to the show. It’s called modern bias, or historical bias. It’s functionally the same thing as cultural bias, judging a radically different culture as if your own experience is the measure for everyone else in the world. The problem is that cultural bias is a lot easier to adjust for than the historical version, because it’s a lot harder for past generations to correct the mistaken impressions of the present.

The issue in Agent Carter is not that the sexism is exaggerated. Far from it. It’s actually pretty accurate, perhaps even toned-down — rather like how the racism of the same period is usually severely toned-down in historical entertainment, to the point that modern audiences don’t even realize that the racism of yesterday is completely alien to today. (Hint: today, blacks can try on clothing before buying it, and can return it later if they change their minds. Think about that.) No, the issue is that the sexism is presented with the clear bias of the 21st century, where it’s a given that anyone who suggests that a woman is incapable of making her own choices is met, rightly, with scorn. Since that is a given, any man who acts otherwise must be an idiot . . . even in an historical period where very few people gave gender roles a second thought.

Yet the problem I have is, again, not that it’s there, but rather that it isn’t presented in the correct way for a modern audience for whom this is almost as alien as seating arrangements based on skin pigmentation. The male antagonists aren’t just unthinkingly protective and chauvinistic; they’re actively arrogant and condescending. Chief Dooley doesn’t just mentally separate “men’s work” and “women’s work”; he berates Peggy Carter as if being a woman is the worst thing in the world.

The one male agent who is in any way on her side is Daniel Sousa, played by the quite excellent Enver Gjokaj. However, when he attempts to point out that the other agents owe Carter an apology, she tears him a new one. He wasn’t trying to treat her any differently than a male agent; it’s quite clear that she’d be owed the same apology if she were a man. It’s driven home in the exact same scene because the same agent insults Sousa for being a cripple (as Sousa lost his leg in the war). Yet insisting on common decency in the workplace, much less in life, is met with scorn by everyone, including the woman in question.

The scene played out like someone was marking off a checklist. Dumb male coworkers? Check. One coworker who tries to be the male protector? Check. Male protector’s head bitten off for implying she can’t hack it even though that’s clearly not what he meant? Check check.

I’m a cripple myself. I’ve been in situations like that. I know firsthand that people who try to help out can be idiots. Condescension doesn’t get any better when the other person means well by it. Yet there are situations where pointing out the flaws in another person’s attitude requires letting that same person know that the wronged party isn’t just being sensitive — that other people noticed it too, and consider it Very Not Cool.

One example from my own past was in college, when a blustering idiot (he got better) decided that I was a hypochondriac and just faking my condition. (Because apparently giving up martial arts, jogging, hiking, and a good measure of my own independence is worth a little sympathy. Or maybe he thought struggling to walk with a cane was just so awesome that everyone wanted to do it.) Word of the confrontation got around, especially around the ladies’ dorms. He suffered a bit of a cold shoulder as a result. Was that a situation when people came to my “rescue”? No. That was where other human beings demanded that one of their fellows act with decency. I was grateful, not because I was incapable of defending myself, but because I was incapable of making a point like that on my own. No one can make a point like that on their own.

So I am not disappointed that it’s a plot point. I’m glad it’s a plot point, because it’s integral to the setting. It’s actually one of the things I was looking forward to. I enjoy the anachronism of a female secret agent in the mid-40s the same way I enjoy said agent’s anachronistic hand-to-hand combat skills. (I might be a stickler for historical details, but it’s always fun to shake up said details within a coherent plot.) What I find disappointing is the ham-handed approach to this particular aspect of the story.

After I finished the third episode, I went back to the original Agent Carter short film and rewatched it. It turns out my memory wasn’t faulty at all. The demonstration of sexism in that particular Marvel One-Shot was quite different than in the Agent Carter TV show. Not only was it the unthinking bigotry (as opposed to outright persecution) that is appropriate to the setting, but there was another difference that I had forgotten: Agent Peggy Carter stood up for herself. She shot back an insult at her section chief after he berated her (and said berating was for showing up the rest of them, rather than for being slow with the coffee), clearly prepared to do what she saw as her duty, rather than letting them walk all over her in the apparent hope that they will respect her if she doesn’t call them on it. (Do note: that never works. And in a story, it makes that character look weak.)

After I finished the third episode, I went back to the original Agent Carter short film and rewatched it. It turns out my memory wasn’t faulty at all. The demonstration of sexism in that particular Marvel One-Shot was quite different than in the Agent Carter TV show. Not only was it the unthinking bigotry (as opposed to outright persecution) that is appropriate to the setting, but there was another difference that I had forgotten: Agent Peggy Carter stood up for herself. She shot back an insult at her section chief after he berated her (and said berating was for showing up the rest of them, rather than for being slow with the coffee), clearly prepared to do what she saw as her duty, rather than letting them walk all over her in the apparent hope that they will respect her if she doesn’t call them on it. (Do note: that never works. And in a story, it makes that character look weak.)

I’ve talked before about how the best way to show an extraordinary character is to surround that character with capable people, rather than go the lazy sitcom route of surrounding him or her with mediocre or incompetent characters. In a story, your character is judged more by his or her foils than anything else, so those secondary characters are important. In this story, the fact that Agent Carter is surrounded by men who look down on her actually takes away from her successes in the field, because if the audience is encouraged to look down on them, it’s hard to see them as proper challenges.

It wouldn’t take much to adjust it. All it takes is a tweak to Enver Gjokaj’s character. It’s already mostly there anyway. Instead of him attempting to stand up for her, per se, he should simply make a point of treating her with the exact same respect given to the male agents. Aside from that one scene, and a bit in a shared moment between them in a file room, he’s basically been “one of the guys,” subject to almost exactly the same scorn as everyone else in the office. Carter even describes how she thinks of him in the third episode, where she says she can almost stomach Sousa getting credit for her successes. The only man she doesn’t appear to look down on is Captain America, and even there it’s tarnished by the popular perception (even in The Captain America Adventure Hour radio show, where “Betty Carver” is a useless woman who only exists to be rescued by her boyfriend) that she’ll never be more than the war hero’s girlfriend.

With ham-handed checkboxing like that, I find little to wonder about when I hear men aren’t interested in the show. Neither gender can be expected to like it when their half of the human species is being presented in a bad light. When Carter is going around actively disliking any male involvement — even that of Jarvis, who’s really the only decent male character in the show — there isn’t much for a male audience member to latch on to. Add that to the incidental characters, like the scornful and insulting male patrons at Carter’s favorite diner, and it can easily seem like there’s an anti-male agenda going on with this show.

And that’s really too bad, because it is an excellent show. I hadn’t expected Carter to have to dodge her own “allies” in order to carry out her own mission. That in and of itself would provide the necessary tension in the SSR setting, without adding in any setting-required sexism at all. After all, it works in modern shows and movies. It’s a successful trope without much risk of cliche because it adds drama and ups the stakes.

Agent Carter is what Agents of SHIELD tried to be: a superhero show where no one has any powers. She lives a double life, has to maintain a cover, and has to think on her feet and move between the rules. This then gets complicated by having to turn things into a triple-life, maintain two covers, and to work with significantly less and/or different support than she’s used to.

It’s an excellent action show, as well as a very good period drama. It’s Foyle’s War meets The Avengers (by which I don’t mean the Marvel Comics characters), with just a dash of James Bond for seasoning. I’m confident that if it weren’t for the checkboxing, you’d have a show with wide appeal, and I hope that we’ll see a bit less of that as time goes on.

If a show depicted all its female characters as negatively as AC does with its male character the studio would be picketed. The show is down right misandrist. I’ll stick with the vastly superior Agents of Shield.

LikeLike